After a decade or extra the place Single-Web page-Functions generated by

JavaScript frameworks have

change into the norm, we see that server-side rendered HTML is turning into

fashionable once more, additionally because of libraries similar to HTMX or Turbo. Writing a wealthy net UI in a

historically server-side language like Go or Java is no longer simply attainable,

however a really engaging proposition.

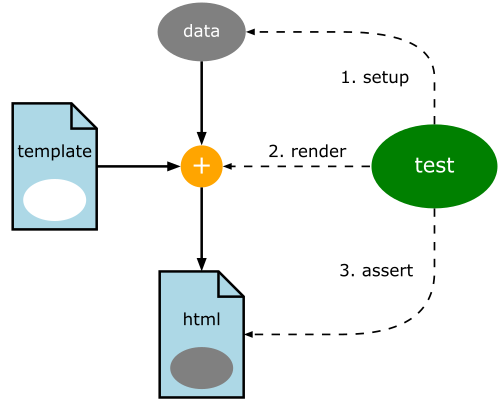

We then face the issue of the way to write automated checks for the HTML

elements of our net functions. Whereas the JavaScript world has advanced highly effective and subtle methods to check the UI,

ranging in measurement from unit-level to integration to end-to-end, in different

languages we don’t have such a richness of instruments accessible.

When writing an internet software in Go or Java, HTML is usually generated

via templates, which comprise small fragments of logic. It’s definitely

attainable to check them not directly via end-to-end checks, however these checks

are sluggish and costly.

We are able to as a substitute write unit checks that use CSS selectors to probe the

presence and proper content material of particular HTML parts inside a doc.

Parameterizing these checks makes it simple so as to add new checks and to obviously

point out what particulars every check is verifying. This method works with any

language that has entry to an HTML parsing library that helps CSS

selectors; examples are supplied in Go and Java.

Motivation

Why test-drive HTML templates? In spite of everything, essentially the most dependable strategy to test

{that a} template works is to render it to HTML and open it in a browser,

proper?

There’s some fact on this; unit checks can not show {that a} template

works as anticipated when rendered in a browser, so checking them manually

is critical. And if we make a

mistake within the logic of a template, often the template breaks

in an apparent approach, so the error is shortly noticed.

Alternatively:

- Counting on guide checks solely is dangerous; what if we make a change that breaks

a template, and we do not check it as a result of we didn’t assume it might impression the

template? We might get an error at runtime! - Templates usually comprise logic, similar to if-then-else’s or iterations over arrays of things,

and when the array is empty, we frequently want to indicate one thing totally different.

Guide checking all instances, for all of those bits of logic, turns into unsustainable in a short time - There are errors that aren’t seen within the browser. Browsers are extraordinarily

tolerant of inconsistencies in HTML, counting on heuristics to repair our damaged

HTML, however then we’d get totally different leads to totally different browsers, on totally different units. It is good

to test that the HTML buildings we’re constructing in our templates correspond to

what we predict.

It seems that test-driving HTML templates is simple; let’s have a look at the way to

do it in Go and Java. I will likely be utilizing as a place to begin the TodoMVC

template, which is a pattern software used to showcase JavaScript

frameworks.

We are going to see strategies that may be utilized to any programming language and templating know-how, so long as now we have

entry to an acceptable HTML parser.

This text is a bit lengthy; it’s your decision to check out the

ultimate answer in Go or

in Java,

or leap to the conclusions.

Stage 1: checking for sound HTML

The primary factor we need to test is that the HTML we produce is

principally sound. I do not imply to test that HTML is legitimate in response to the

W3C; it might be cool to do it, nevertheless it’s higher to begin with a lot easier and quicker checks.

As an illustration, we wish our checks to

break if the template generates one thing like

<div>foo</p>

Let’s examine the way to do it in levels: we begin with the next check that

tries to compile the template. In Go we use the usual html/template package deal.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

_ = templ

}

In Java, we use jmustache

as a result of it is quite simple to make use of; Freemarker or

Velocity are different frequent decisions.

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

}

If we run this check, it’ll fail, as a result of the index.tmpl file does

not exist. So we create it, with the above damaged HTML. Now the check ought to move.

Then we create a mannequin for the template to make use of. The appliance manages a todo-list, and

we will create a minimal mannequin for demonstration functions.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

_ = templ

_ = mannequin

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

}

Now we render the template, saving the leads to a bytes buffer (Go) or as a String (Java).

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, mannequin)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(mannequin);

}

At this level, we need to parse the HTML and we count on to see an

error, as a result of in our damaged HTML there’s a div component that

is closed by a p component. There’s an HTML parser within the Go

normal library, however it’s too lenient: if we run it on our damaged HTML, we do not get an

error. Fortunately, the Go normal library additionally has an XML parser that may be

configured to parse HTML (because of this Stack Overflow reply)

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

// render the template right into a buffer

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, mannequin)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// test that the template may be parsed as (lenient) XML

decoder := xml.NewDecoder(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

decoder.Strict = false

decoder.AutoClose = xml.HTMLAutoClose

decoder.Entity = xml.HTMLEntity

for {

_, err := decoder.Token()

swap err {

case io.EOF:

return // We're carried out, it is legitimate!

case nil:

// do nothing

default:

t.Fatalf("Error parsing html: %s", err)

}

}

}

This code configures the HTML parser to have the fitting degree of leniency

for HTML, after which parses the HTML token by token. Certainly, we see the error

message we needed:

--- FAIL: Test_wellFormedHtml (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:61: Error parsing html: XML syntax error on line 4: sudden finish component </p>

In Java, a flexible library to make use of is jsoup:

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(mannequin);

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

}

And we see it fail:

java.lang.AssertionError: Anticipating empty however was:<[<1:13>: Unexpected EndTag token [</p>] when in state [InBody],

Success! Now if we copy over the contents of the TodoMVC

template to our index.tmpl file, the check passes.

The check, nonetheless, is simply too verbose: we extract two helper capabilities, in

order to make the intention of the check clearer, and we get

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

assertSoundHtml(html);

}

Stage 2: testing HTML construction

What else ought to we check?

We all know that the seems of a web page can solely be examined, finally, by a

human how it’s rendered in a browser. Nevertheless, there may be usually

logic in templates, and we wish to have the ability to check that logic.

One is perhaps tempted to check the rendered HTML with string equality,

however this system fails in observe, as a result of templates comprise a number of

particulars that make string equality assertions impractical. The assertions

change into very verbose, and when studying the assertion, it turns into troublesome

to know what it’s that we’re attempting to show.

What we’d like

is a method to say that some elements of the rendered HTML

correspond to what we count on, and to ignore all the small print we do not

care about. A method to do that is by working queries with the CSS selector language:

it’s a highly effective language that permits us to pick the

parts that we care about from the entire HTML doc. As soon as now we have

chosen these parts, we (1) depend that the variety of component returned

is what we count on, and (2) that they comprise the textual content or different content material

that we count on.

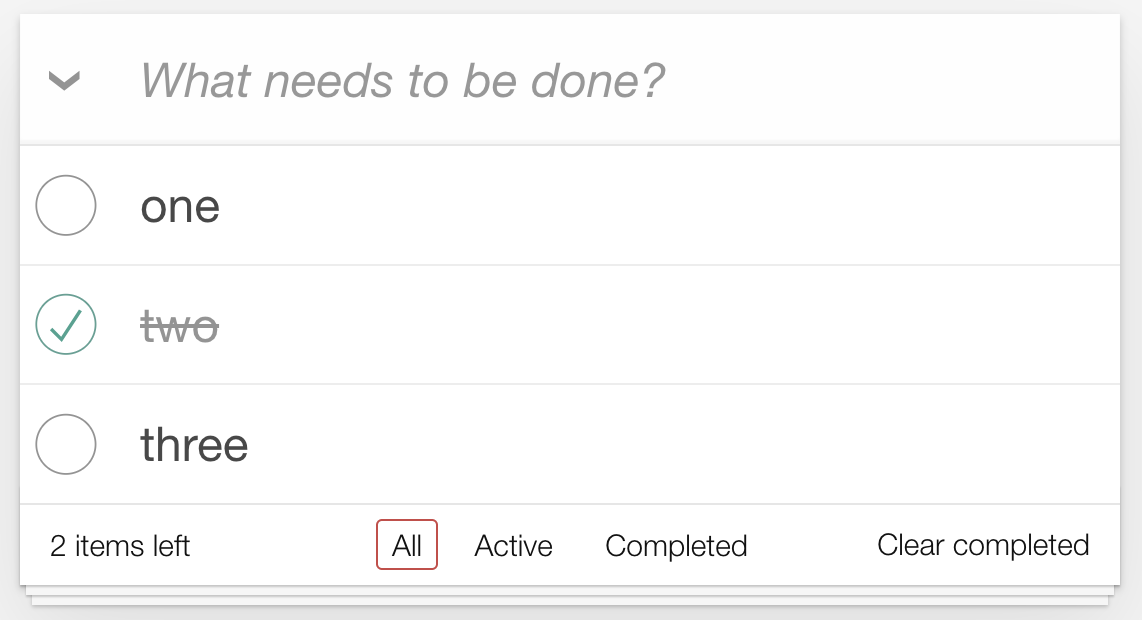

The UI that we’re imagined to generate seems like this:

There are a number of particulars which might be rendered dynamically:

- The variety of gadgets and their textual content content material change, clearly

- The model of the todo-item adjustments when it is accomplished (e.g., the

second) - The “2 gadgets left” textual content will change with the variety of non-completed

gadgets - One of many three buttons “All”, “Energetic”, “Accomplished” will likely be

highlighted, relying on the present url; as an illustration if we determine that the

url that exhibits solely the “Energetic” gadgets is/lively, then when the present url

is/lively, the “Energetic” button must be surrounded by a skinny crimson

rectangle - The “Clear accomplished” button ought to solely be seen if any merchandise is

accomplished

Every of this considerations may be examined with the assistance of CSS selectors.

This can be a snippet from the TodoMVC template (barely simplified). I

haven’t but added the dynamic bits, so what we see right here is static

content material, supplied for instance:

index.tmpl

<part class="todoapp">

<ul class="todo-list">

<!-- These are right here simply to indicate the construction of the record gadgets -->

<!-- Listing gadgets ought to get the category `accomplished` when marked as accomplished -->

<li class="accomplished"> ②

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox" checked>

<label>Style JavaScript</label> ①

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>Purchase a unicorn</label> ①

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

<footer class="footer">

<!-- This must be `0 gadgets left` by default -->

<span class="todo-count"><sturdy>0</sturdy> merchandise left</span> ⓷

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a class="chosen" href="#/">All</a> ④

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/lively">Energetic</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/accomplished">Accomplished</a>

</li>

</ul>

<!-- Hidden if no accomplished gadgets are left ↓ -->

<button class="clear-completed">Clear accomplished</button> ⑤

</footer>

</part>

By trying on the static model of the template, we will deduce which

CSS selectors can be utilized to determine the related parts for the 5 dynamic

options listed above:

| characteristic | CSS selector | |

|---|---|---|

| ① | All of the gadgets | ul.todo-list li |

| ② | Accomplished gadgets | ul.todo-list li.accomplished |

| ⓷ | Objects left | span.todo-count |

| ④ | Highlighted navigation hyperlink | ul.filters a.chosen |

| ⑤ | Clear accomplished button | button.clear-completed |

We are able to use these selectors to focus our checks on simply the issues we need to check.

Testing HTML content material

The primary check will search for all of the gadgets, and show that the info

arrange by the check is rendered appropriately.

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate(mannequin)

// assert there are two <li> parts contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

}

We’d like a strategy to question the HTML doc with our CSS selector; a great

library for Go is goquery, that implements an API impressed by jQuery.

In Java, we hold utilizing the identical library we used to check for sound HTML, particularly

jsoup. Our check turns into:

Go

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

// parse the HTML with goquery

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

// assert there are two <li> parts contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li")

assert.Equal(t, 2, choice.Size())

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

assert.Equal(t, "Foo", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[1]))

}

func textual content(node *html.Node) string {

// A little bit mess as a consequence of the truth that goquery has

// a .Textual content() methodology on Choice however not on html.Node

sel := goquery.Choice{Nodes: []*html.Node{node}}

return strings.TrimSpace(sel.Textual content())

}

Java

@Take a look at

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

// parse the HTML with jsoup

Doc doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "");

// assert there are two <li> parts contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(2);

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

assertThat(choice.get(0).textual content()).isEqualTo("Foo");

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

assertThat(choice.get(1).textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

If we nonetheless have not modified the template to populate the record from the

mannequin, this check will fail, as a result of the static template

todo gadgets have totally different textual content:

Go

--- FAIL: Test_todoItemsAreShown (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:44: First record merchandise: need Foo, bought Style JavaScript

index_template_test.go:49: Second record merchandise: need Bar, bought Purchase a unicorn

Java

IndexTemplateTest > todoItemsAreShown() FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Anticipating:

<"Style JavaScript">

to be equal to:

<"Foo">

however was not.

We repair it by making the template use the mannequin information:

Go

<ul class="todo-list"> {{ vary .Objects }} <li> <div class="view"> <enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox"> <label>{{ .Title }}</label> <button class="destroy"></button> </div> </li> {{ finish }} </ul>

Java – jmustache

<ul class="todo-list"> {{ #allItems }} <li> <div class="view"> <enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox"> <label>{{ title }}</label> <button class="destroy"></button> </div> </li> {{ /allItems }} </ul>

Take a look at each content material and soundness on the similar time

Our check works, however it’s a bit verbose, particularly the Go model. If we’ll have extra

checks, they may change into repetitive and troublesome to learn, so we make it extra concise by extracting a helper operate for parsing the html. We additionally take away the

feedback, because the code must be clear sufficient

Go

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

doc := parseHtml(t, buf)

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li")

assert.Equal(t, 2, choice.Size())

assert.Equal(t, "Foo", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[1]))

}

func parseHtml(t *testing.T, buf bytes.Buffer) *goquery.Doc {

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

return doc

}

Java

@Take a look at

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

var doc = parseHtml(html);

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(2);

assertThat(choice.get(0).textual content()).isEqualTo("Foo");

assertThat(choice.get(1).textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

personal static Doc parseHtml(String html) {

return Jsoup.parse(html, "");

}

Significantly better! Not less than for my part. Now that we extracted the parseHtml helper, it is

a good suggestion to test for sound HTML within the helper:

Go

func parseHtml(t *testing.T, buf bytes.Buffer) *goquery.Doc {

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

return doc

}

Java

personal static Doc parseHtml(String html) {

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

var doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

return doc;

}

And with this, we will eliminate the primary check that we wrote, as we are actually testing for sound HTML on a regular basis.

The second check

Now we’re in a great place for testing extra rendering logic. The

second dynamic characteristic in our record is “Listing gadgets ought to get the category

accomplished when marked as accomplished”. We are able to write a check for this:

Go

func Test_completedItemsGetCompletedClass(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.AddCompleted("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

doc := parseHtml(t, buf)

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li.accomplished")

assert.Equal(t, 1, choice.Dimension())

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

}

Java

@Take a look at

void completedItemsGetCompletedClass() {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.addCompleted("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

Doc doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "");

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li.accomplished");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(1);

assertThat(choice.textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

And this check may be made inexperienced by including this little bit of logic to the

template:

Go

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ vary .Objects }}

<li class="{{ if .IsCompleted }}accomplished{{ finish }}">

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>{{ .Title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ finish }}

</ul>

Java – jmustache

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ #allItems }}

<li class="{{ #isCompleted }}accomplished{{ /isCompleted }}">

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>{{ title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ /allItems }}

</ul>

So little by little, we will check and add the varied dynamic options

that our template ought to have.