In his newest e-book, the oncologist and acclaimed author Siddhartha Mukherjee focuses his narrative microscope on the cell, the elementary constructing block from which complicated methods and life itself emerge. It’s the coordination of cells that enable hearts to beat, the specialization of cells that create strong immune methods, and the firing of cells that kind ideas. “We have to perceive cells to grasp the human physique,” Mukherjee writes. “We’d like them to grasp medication. However most primarily, we’d like the story of the cell to inform the story of life and of our selves.”

His account, The Tune of the Cell, reads at occasions like an artfully written biology textbook and at occasions like a philosophical tract. Mukherjee begins with the invention of the microscope and the historic origins of cell biology, from which he dives into mobile anatomy. He examines the hazards of overseas cells like micro organism, and of our personal cells after they misbehave, are hijacked, or fail. He then strikes into extra complicated mobile methods: blood and the immune system, organs, and the communication between cells. “The human physique capabilities as a citizenship of cooperating cells,” he writes. “The disintegration of this citizenship suggestions us from wellness into illness.”

At every step, he’s cautious to attract a transparent line from the invention of mobile capabilities to the therapeutic potential they maintain. “A hip fracture, cardiac arrest, immunodeficiency, Alzheimer’s dementia, AIDS, pneumonia, lung most cancers, kidney failure, arthritis—all might be reconceived because the outcomes of cells, or methods of cells, functioning abnormally,” Mukherjee writes. “And all might be perceived as loci of mobile therapies.”

Understanding how electrical currents have an effect on neurons, for instance, led to experiments utilizing deep mind stimulation to deal with temper problems. And T-cells, the “door-to-door wanderers” that journey by way of the physique and hunt for pathogens, are being skilled to struggle most cancers as medical doctors higher perceive how these wanderers discriminate between overseas cells and the “self.”

Mukherjee, who received a Pulitzer Prize for his 2010 e-book The Emperor of All Maladies, is a fascinating author. He skillfully picks out the human characters and the idiosyncratic historic particulars that can seize readers and maintain them by way of the drier technical sections. Take, for example, his lengthy discourse on the beginner and tutorial scientists who toyed with early microscopes. Amongst descriptions of lenses and petty tutorial fights (some issues, it appears, are everlasting), Mukherjee provides the delectably lewd anecdote that within the seventeenth century, the Dutch dealer and microscope fanatic Antonie van Leeuwenhoek skilled his scopes on, amongst different issues, his personal semen and the semen of somebody contaminated with gonorrhea. In these samples, Leeuwenhoek noticed what he known as “a genital animalcule,” and what we now name spermatozoa, “transferring like a snake or an eel swimming in water.”

Simply as Mukherjee attracts clear connections between scientific discoveries and potential therapeutics, he additionally excels at displaying the excessive stakes of those therapies by drawing on case research and vivid examples from sufferers he’s seen over the course of his profession. There may be Sam P., who jokes that his fast-moving most cancers will unfold by the point he walks to the lavatory; and M.Okay., a younger man ravaged by a mysterious immune dysfunction, whose father trekked by way of the snow to Boston’s North Finish to purchase his son’s favourite meatballs and ferry them to the hospital.

And there may be Emily Whitehead, who, as a toddler, suffered from leukemia and whose cells are saved inside a freezer named after “The Simpsons” character Krusty the Clown. Some cells had been genetically modified to acknowledge and struggle off Whitehead’s illness. The success of that remedy, known as CAR-T, heralded a change in most cancers therapies and Whitehead turned the miraculously wholesome results of centuries of scientific inquiry. “She embodied our need to get to the luminous coronary heart of the cell, to grasp its endlessly charming mysteries,” Mukherjee writes. “And he or she embodied our aching aspiration to witness the start of a brand new sort of medication—mobile therapies—based mostly on our deciphering the physiology of cells.”

As if forays into oncology, immunology, pathology, the historical past of science, and neurobiology weren’t sufficient, Mukherjee additionally will get to actually large questions in regards to the ethics of mobile therapies, the that means of incapacity, perfectionism, and acceptance in a world the place all bodily options is perhaps altered—and even the character of life itself. “A cell is the unit of life,” he writes. “However that begs a deeper query: What’s ‘life?’i”

In some methods, the cell is the proper vessel by which to journey down these many winding, diverging, and intersecting paths. Cells are the positioning of some unbelievable tales of analysis, discovery, and promise, and Mukherjee provides himself ample room to research a various array of organic processes and interventions. However in making an attempt to embody all the pieces that cells may be and do—each metaphorically and actually—Mukherjee finally ends up failing to completely discover these deep questions in a satisfying manner.

It doesn’t assist that he leans so closely on metaphor. The cell is a “decoding machine,” a “dividing machine,” and an “unfamiliar spacecraft.” He likens cells to “Lego blocks,” “corporals,” “actors, gamers, doers, staff, builders, creators.” T-cells alone are described as each a “gumshoe detective” and a “rioting crowd disgorging inflammatory pamphlets on a rampage.” To not point out the various cell metaphors Mukherjee quotes from others. Creating imagery readers can perceive is a useful a part of any science author’s playbook, however so many photographs may also be distracting at occasions.

The ultimate part grapples with the implications of enhanced people who profit from mobile tinkering. These “new people” should not cyborgs or folks augmented with superpowers, Mukherjee clarifies. When introducing the thought on the outset of the e-book, he writes, “I imply a human rebuilt anew with modified cells who seems and feels (largely) such as you and me.” However by engineering stem cells in order that an individual with diabetes can produce their very own insulin or implanting an electrode within the mind of somebody struggling with melancholy, Mukherjee posits that we’ve modified them in some basic manner. People are a sum of their elements, he writes, however cell therapies cross a border, remodeling folks right into a “new sum of recent elements.”

This part echoes a well-known philosophical thought experiment in regards to the Ship of Theseus. Theseus left Athens in a wood ship that, over the course of a protracted journey, needed to be repaired. Sailors eliminated rotting wooden and changed the damaged oars. By the point the ship returned, not one of the unique wooden remained. Philosophers have debated the character of the ship for hundreds of years: Is the repaired ship the identical because the one which left Athens or is it a brand new ship altogether?

The identical query is perhaps requested of Mukherjee’s “new people.” What number of cells have to be altered as a way to render us new? Do sure cells matter greater than others? Or do people possess some sort of inherent integrity—a conscience, a soul—that impacts these calculations?

Mukherjee by no means totally arrives at a solution, however his e-book’s title could allude to at least one, recalling Walt Whitman’s Tune of Myself, an ode to the interconnectedness of beings. Mukherjee urges scientists to desert the “atomism” of analyzing solely remoted items—be they atoms, genes, cells—in favor of a complete strategy that appreciates the entire of a system, or of a being. “Multicellularity developed, repeatedly, as a result of cells, whereas retaining their boundaries, discovered a number of advantages in citizenship,” he writes. “Maybe we, too, ought to start to maneuver from the one to the various.”

This text was initially revealed on Undark. Learn the unique article.

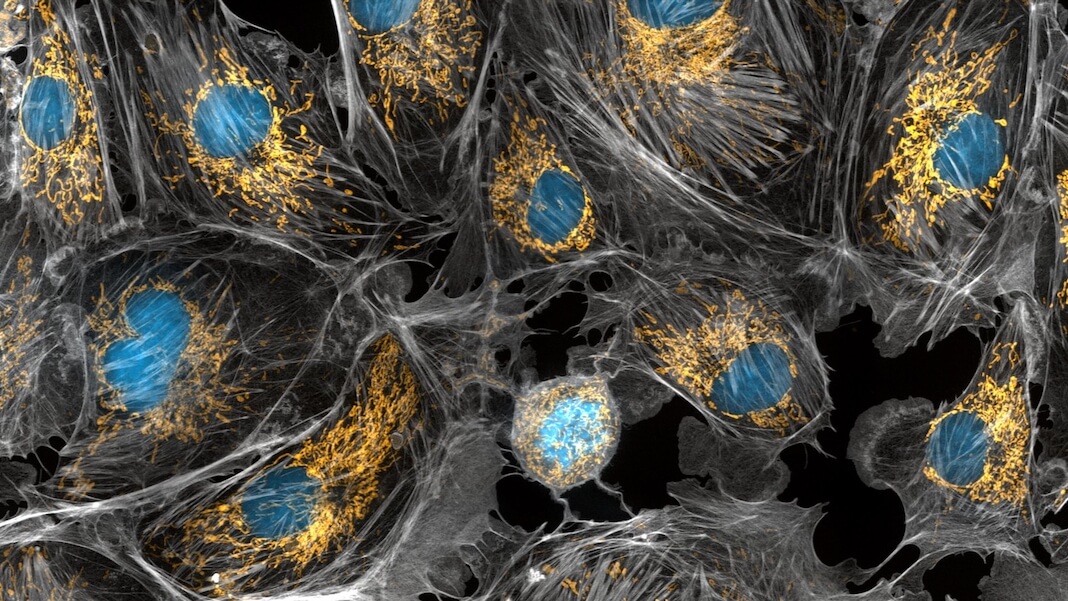

Picture Credit score: Torsten Wittmann, College of California, San Francisco through NIH on Flickr